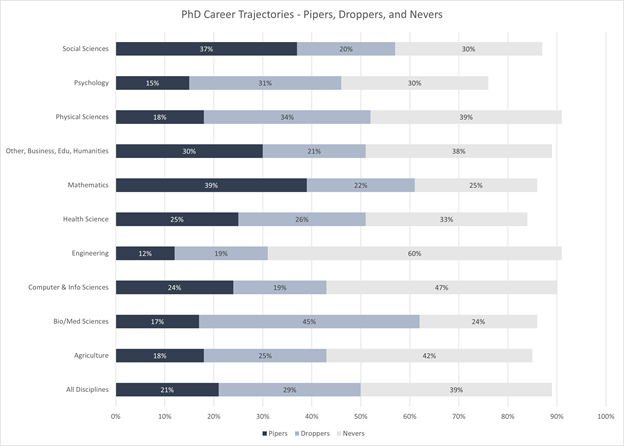

A couple of weeks ago I can across a new paper showing the career trajectories of nearly 10,000 PhDs over the last decade. Only about 20-30% of PhDs begin and remain on an academic path as a professor. The majority of doctors either leave for the mysterious “industry” career right out of their programs, after post-docing, or pre-tenure. There’s a lot of reasons why – poor pay and long hours contributing for many – but also because there are just not enough jobs.

As someone who aspired for an academic career on the tenure-track and ended up leaving for a non-professor career (at the intersection of education, tech, and non-profit), it’s comforting to know that many – most – PhDs end up in the same boat.

This was not always the case, however. Pre-World War II, PhDs were relatively rare in the population as compared to now, and most who aspired to be a professor carried on through their programs until their advisor called their friend at university X to get them a position. During the post-World War II higher education expansion, universities couldn’t hire enough professors, and most didn’t even hold PhDs. Starting in the 70s and 80s higher ed went though a change, and today hundreds of PhDs apply for single job openings, with many having their dreams crushed in the process.

It’s fascinating to read about higher ed history. On the one hand things are entirely different. On the other, everything is the exact same. In An Academic Life: A Memoir, Hanna Holborn Gray shows exactly how both of those statements are true.

In many ways, Gray lived the quintessential academic life in the post-war boom. Growing up as an immigrant in America after her family fled from Nazi Germany, Gray was immersed in academics. The daughter of two professors, she was no stranger to university life. She entered college at Bryn Mawr during the post war years, and went on to study for a year at Oxford University, before returning to America to earn her doctorate at Harvard (technically Radcliffe College at the time for women only). She began her career at the University of Chicago before moving into administration at Evanston then Yale, until returning to the University of Chicago as President in 1978.

Across her journey, there are no stories of a stressful academic job market, the submission of 10+ documents and statements, or anything that resembles the modern PhD job hunting experience today. The other side of that coin, however, is the sexism and segregation during her career that makes her accomplishments in leadership positions at top universities even more impressive.

Aside from these clear differences, however, there are notable similarities to today’s “crisis” of free speech on college campuses. Censorship and politicization of the academy – the antithesis of the classical liberal ideal of higher education – have been around since at least the 60s and were notable during the cold war period. Since the mid 2010s, college campuses have again been embroiled in political and cultural controversy. Everything is different, yet also the same.

An Academic Life was an enjoyable memoir of the quixotic academic career that seems to no longer exist. I particularly enjoyed learning of her experience with as an administrator in dealing with the culture wars of the day. It’s a topic I find fascinating because it seems to be a constant feature of academia despite the idealist open-inquiry institution it wishes to (and should) be.

Published: August 2018

Format: Hardcover

If you think this sounds interesting, bookmark these other great reads:

Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell by Jason Riley (2021)

The Last Negroes At Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever by Kent Garett and Jeanne Ellsworth (2020)

A Perfect Mess: The Unlikely Ascendancy of American Higher Education by David Labaree (2018)

This post contains affiliate links, allowing me to earn a small commission when you purchase books from the link provided. There is no cost to you, and this will allow me to keep this newsletter free and open to all. Happy reading!